€urope’s role in the €nergy €volution

Gordon Bennett

Managing Director, Utility Markets, ICE

Takeaways

- Moving to a global renewable energy economy will be a long road

- As the cleanest fossil fuel which is cost efficient, natural gas supports the needs of energy-poor nations as a ‘partner fuel’ to renewables

- Market-based mechanisms - such as the EU’s emissions trading scheme - enable participants to quantify decisions around energy use

Europe’s energy strategy aims to achieve a trilogy of interdependent objectives: secure, competitive, and sustainable energy, to help address the impact of climate change. This is underpinned by the ‘clean energy for all Europeans’ package and Europe’s commitment to the Paris Agreement.

Already, the continent’s natural gas and emissions markets have been critical in its shift toward cleaner energy and meeting its policy objectives. Now, these markets are poised to expand their role globally, as the road to a low carbon future drives demand for cleaner energy, and the need to accurately price greenhouse gas emissions.

The European Union Emission Trading Scheme (EU ETS) was the first and continues to be the largest Emissions market globally. This cornerstone of the EU’s climate policy provides transparent pricing in euros, helping to cut emissions in a cost efficient manner.

Europe’s natural gas markets are an indispensable partner in the transition to renewable energy. As an affordable, cleaner alternative to other fossil fuels, natural gas can help meet rising demand from countries in Africa and Asia, where the cost and intermittent nature of renewables make them unsuitable for a primary energy source.

Europe and natural gas globalization

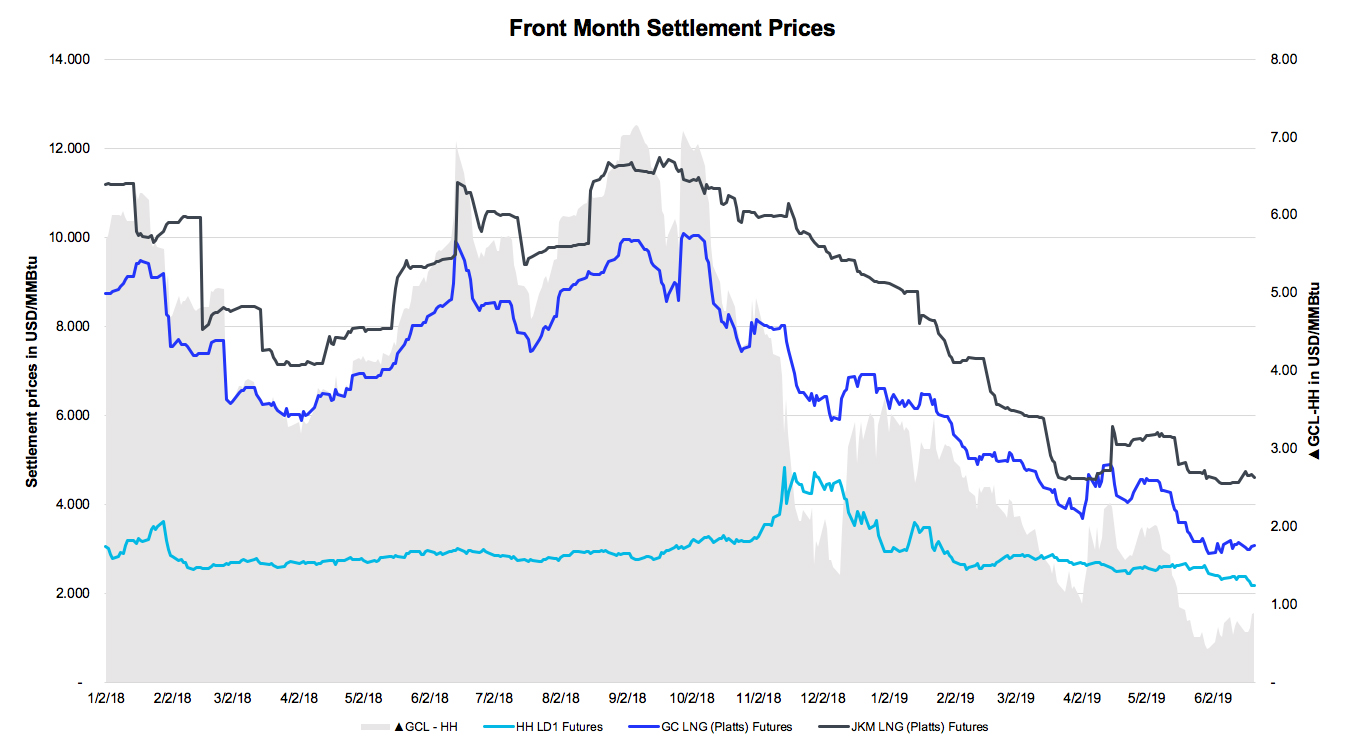

Natural gas markets traditionally reconciled supply and demand on a regional level in the U.S., Europe and Asia. This order is being disrupted by surging shale production in North America which has made the U.S. a key LNG exporter, while Asia’s long-term legacy oil-indexed LNG contracts are unwinding. As a result, producers are no longer tied to destination-specific contracts or oil-indexation, and natural gas is evolving to become a truly global commodity - subject to free market supply and demand dynamics.

This evolution calls for globally recognized natural gas benchmarks in key demand and supply centers, to ensure that LNG finds its way to the most willing buyers.

The Title Transfer Facility (TTF) market has developed into Europe’s leading natural gas benchmark, following its establishment in 2003 to enhance the liquidity of the Dutch gas market. Modelled on Europe’s first actively traded natural gas market - the sterling-denominated National Balancing Point (NBP) - its rise was gradual. For several years after its establishment, the TTF was thinly traded and only gained traction after the European Commission’s Third Energy Package was introduced and the Netherlands developed the TTF into the ‘Gas Roundabout’ of Europe. This development was accelerated by the oversupply of natural gas at the end of the last decade, which translated into low spot prices and made legacy oil-indexed purchase agreements untenable, as gas and oil prices decoupled.

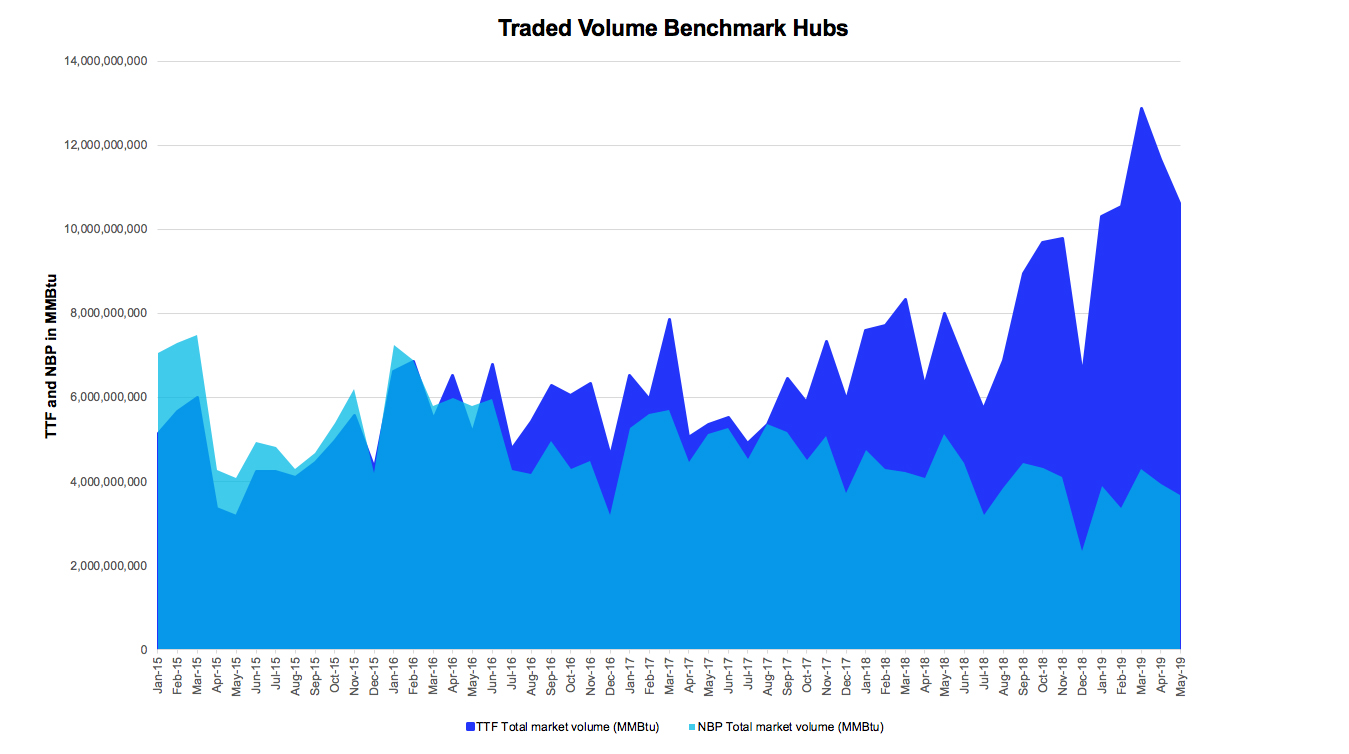

Hub based gas-on-gas pricing became the norm in Northwest Europe, further boosting liquidity of the forward market, with a preference for euro-denominated contracts on the TTF. From 2009 to 2011, TTF’s traded volumes rose by an average of over 62% per year. Since 2016 it has outstripped NBP allowing it to gain the moniker of the “Brent of natural gas”. While NBP has retained its status as an important secondary source of forward liquidity, TTF’s position as Europe’s natural gas benchmark has been cemented.

The ocean transport of LNG creates a virtual pipeline between demand and supply centers of natural gas in the U.S., Africa, Europe and Asia. As a result, these regional markets are becoming increasingly interconnected - with a larger number of new LNG deals referencing the TTF market, including those in Asia. The globalization of natural gas has elevated Europe’s importance as the world’s LNG balancing market, with strong volume growth for TTF reflecting this internationalization.

Meanwhile, the status of North America’s Henry Hub is under threat as it diverges from natural gas prices at key shale basins - supporting the rise of regional basis markets which are more representative. Low and globally disconnected natural gas prices have also thrown Henry’s relevance into question: in a pre-global gas market, Henry-indexed contracts meant a price advantage for buyers. Now, tighter margins mean that new U.S. export facilities will find it problematic to tie themselves to the marker, as a global market with cheaper prices in Europe and Asia make the practice uneconomical.

What is TTF?

- The Title Transfer Facility (TTF) is a virtual trading hub, where participants can transfer the title on natural gas in the transmission system to other market players

- The Euro-denominated marker can absorb excess supply of LNG not sold in Asia - acting as the world’s balancing market

- As a liquid natural gas hub with global relevance, TTF is well-positioned to play a key role in the energy transition

TTF takes center stage

Capitalizing on the rise of TTF as Europe’s natural gas benchmark means avoiding the dilution of liquidity towards other hubs. Yet rivals to a lead benchmark remain. Germany has plans to challenge the TTF through the merger of its NCG and Gaspool hubs, which would bring together two existing illiquid markets. However the merger has been criticised by market participants as being costly, complex, and is not expected to achieve any significant improvement in German natural gas market liquidity. In addition, market participants argued that TTF already enables them to hedge exposure to German gas markets. The German energy regulator BNetzA and industry have also recognized that any integration of both German market areas should include TFF to have any meaningful effect on market liquidity.

More broadly, support for a European natural gas benchmark will come from the continent’s ongoing shift from oil-on-gas to gas-on-gas pricing - including initiatives to encourage the end of oil-indexation in Southern and Eastern Europe. Addressing physical capacity constraints in the EU (e.g. between France and Spain) would bolster the creation of a single European gas market by supporting increased price convergence across Europe. Further policy support for a single European gas benchmark would come from full implementation of existing EU gas directives, which should further liberalise the EU’s gas and power markets.

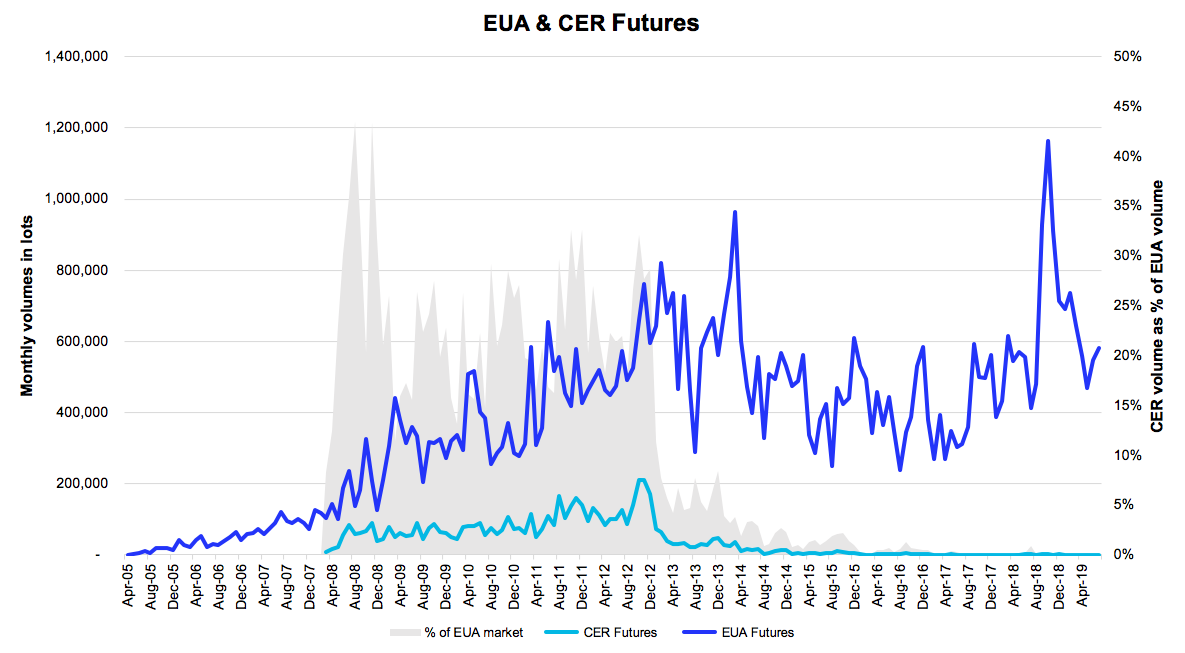

The EU carbon market - global leadership

As the cornerstone of Europe’s climate policy, the ETS has shown tremendous resilience since its launch in 2005. The recent ETS Phase IV revisions and Market Stability Reserve - which addresses surplus allowances and improves the system's shock resilience - help assure its future as a key component of the energy transition. Europe’s success in establishing the world’s largest international carbon market has inspired similarly designed schemes around the world, from California to China.

By continuing to promote the linkage of third country emission trading schemes to that of the EU, deep liquidity in the secondary ETS market could be further advanced. Switzerland is a recent addition, and will link its emissions trading scheme to the EU’s in 2020. Linking emissions trading systems is a long-term goal for the EU, and helps cut the cost of fighting climate change.

The lack of a coherent primary energy policy has led to a diverse generation stack in Europe, with inconsistent outcomes for EU climate policy. With natural gas recognized as an ideal partner fuel in transitioning to a low carbon economy in Europe and Asia, more emphasis should be put on a European primary energy policy. Part of that consideration could include promoting the broader use of LNG in areas such as transportation fuel.

Although the creation of a global carbon price may be challenging in the medium term, the EU is well placed to build its position as home to the world’s largest carbon market. Longer term, establishing a replacement for Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) developed by the introduction of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) - could support a truly international carbon market. Already, the Paris Agreement’s Article 6 represents a potential replacement: a legal framework for a market-based mechanism at a regional and international level. Procedures for Article 6 and the rest of the Paris Agreement are still being negotiated, ahead of the 2019 Conference of Parties (COP) in Chile. The 2020 COP in Europe is likely to be a critical summit, marking full adoption of the Paris Accord and the deadline to strengthen national action plans.

More broadly, market-based mechanisms will be crucial to help quantify the cost of polluting. The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme is experienced in the design and operation of these markets, with anticipation around additional mechanisms via the Paris Agreement. And as business leaders and policy makers grapple with the consequences of climate change, the effective use of these tools - and the ability to meet developing nations’ energy needs - will ultimately dictate the success of the energy transition.

The transition to a zero carbon economy will be a long and uncertain road - and one that moves in stages - as it dictates a new preference for primary energy sources. While the higher cost of renewables may be feasible for developed nations, energy-poor countries will prioritize reliable and cost-efficient sources. To meet this demand, natural gas is a key ‘partner fuel’, with markers such as TTF being ideally placed.