As the executive summary explains, the purpose of this report from Energy Intelligence is to provide a deep dive into the role of the Brent and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil benchmarks, their mutual relationship, and their interaction with the global oil market.

Part two of the series below delves into why the world needs benchmarks and what characteristics they obtain.

Why the world needs benchmarks

The need for price discovery

Of all global commodities, the global crude oil trade is unique for its size, scope and complexity. Hundreds of different grades of crude oil are going to around 700 refineries in all corners of the world. No other commodity has such reach. The value of oil traded also puts all other commodities in its shadow. Crude oil produced in 2019 had a value of roughly $1.6 trillion.

Each crude oil from each field has a unique quality. To create some order, they are grouped together as light or heavy and sweet or sour grades. Crudes that are light (less dense) and sweet (low sulfur) are the easiest to refine into products. Some crude grades yield more gasoline, others more diesel. Ultimately, all crudes can make all products, and around the world these products are essentially the same.

It is the value of the refined products that ultimately determines the value of the crude oil that makes them. If a crude oil is good at making gasoline, and gasoline has a strong value that will make this crude oil attractive to buy and refine.

The basic concept is straightforward, but the actual process to assess the value of crude oil involves an intricate maze of steps and decisions. The consumer sends signals to refineries about what products are needed. A refinery then shops around and buys, at the best available price, the crude oil that can make the product. Sometimes that crude oil is at the other side of the world.

- Refiners need meaningful price signals to quickly assess the value of a crude. Those signals come from the oil spot market where around 40 million barrels move around the world every day. To distill price clarity from the large variety of oils on offer and the large group of players, the market created benchmarks.

- Benchmarks are critical in defining the spot value of crude, help determine the price for crude oil sold under term contracts, are the basis for hedging and risk management and attract lots of managed money to oil markets.

- Over time, Brent in the North Sea evolved as the global benchmark — the oil price for all to see. Brent is “the price of oil.” It is the Brent price that allows other grades in various regions to determine their own value quickly, based on price relationships that different grades have established over time. In North America, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) is a benchmark. In the Middle East, Dubai and Oman are benchmarks. They all essentially trade at a differential to Brent.

- The oil market is relatively young and still evolving; its spot pricing mechanism is even younger. The spot market for oil, which is at the basis of all price discovery, has only developed since the early 1980s. Supporting the development of the spot market was the rise of benchmark grades. As they provided the quick reference price level for similar crude oils, benchmarks helped a rise in market liquidity.

- The spot market, which captures 40% of internationally traded crude oil, is essentially trading oil cargoes for immediate delivery. That way, the spot market allocates scarce or abundant supplies in an economically efficient manner. A key characteristic of the spot market is that it is pricing the marginal barrel of oil available. The last trade sets the price of oil. That way, the market reflects demand and supply.

- The benchmark status of Brent and WTI is supported by their highly liquid electronic futures exchanges. Brent advanced as the global benchmark from 2010 after WTI price dislocations, due mainly to pipeline constraints.

- It is the relationship between the physical and paper markets where price discovery takes place. In the interaction between the ICE Brent Futures contracts and the physical market in the North Sea, the world settles on “the price of oil.” In the end, oil prices are the result of supply and demand. To get there, all the players in the market have their say: producers, consumers, refiners, physical traders, banks, funds, and other types of investors that see oil as a tool to express their market expectations. Because of its strategic importance, crude oil has always had political overtones beyond its economic value.

Refiners need meaningful price signals to quickly assess the value of a crude. Those signals come from the oil spot market where around 40 million barrels move around every day. To distill price clarity from the large variety of oils on offer and the large group of players, the market created benchmarks. They represent a reference level for crudes of roughly the same quality in the same location.

Over time, Brent in the North Sea evolved as the global benchmark — the oil price for all to see. Brent is “the price of oil.” It is the Brent price that allows other grades in various regions to determine their own value quickly, based on price relationships that different grades have established over time. In North America, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) is a benchmark and it still has a wide appeal beyond its region for the liquid futures contract market. In the Middle East, Dubai and Oman are benchmarks. They all essentially trade at a differential to Brent.

Evolution of oil trade

The oil market is relatively young and still evolving; its spot pricing mechanism is even younger. The spot market for oil, which is at the basis of all price discovery, has only developed since the early 1980s. Its emergence turned the way oil was priced on its head. The old pricing regime was straightforward. A few participants set the price of oil. In the 15 years before the spot market became dominant, the price of virtually all oil that changed hands in the world was set by the governments of oil-exporting countries. In the 1950s and 1960s, major international oil companies effectively controlled world oil markets.

"Benchmarks are critical in defining the spot value of crude, help determine the price for crude oil sold under term contracts, are the basis for hedging and risk management and attract lots of managed money to oil markets."

The old pricing system represented a vertically integrated industry that sold most oil under term contracts at set prices. The system was gradually broken up by a number of shocks. The Arab oil embargo in 1973, the Iranian revolution in 1979, nationalizations of companies in producing states and the growth of independent oil companies and international traders all changed the character of the industry and the oil trade. They allowed for the spot market to take center stage as the main barometer for international oil prices.

In the 1970s, the vertically integrated systems fell apart. While oil producing had moved into the hands of producing governments, the marketing and refining of oil was still held by international oil firms. That gap in the supply chain was gradually filled by the spot market. Specialized oil trading and brokerage firms that had mainly dealt with refined products shifted their focus to crude oil. Traders that previously dealt with metal, grain or wool brought their expertise to the oil market.

The spot market represented just a trickle of sales, initially, but had grown to one-third of all oil sales in the mid-1980s. By the late 1980s, almost all internationally traded oil was linked to prices in the spot market. Oil producers in the Middle East continued selling most of their oil via term contracts, but the term-contract price was set as a differential to the value of a regional benchmark. That system holds to this date.

Supporting the development of the spot market was the rise of benchmark grades. As they provided the quick reference price level for similar crude oils, they helped a rise in market liquidity. Saudi Arabia’s Arab Light and UK Forties were the first benchmark grades. Brent was added in the early 1980s. Riyadh suppressed spot trade in the early 1980s, allowing Dubai to rise as a regional marker. In 1983, US WTI became a benchmark after it was selected as the main reference grade for the new NYMEX crude oil futures contract and evolved as the global marker. Dubai and Oman developed as key price links for oil sales to Asia. The benchmark status of Brent and WTI was supported by their highly liquid electronic futures exchanges. Brent advanced as the global benchmark from 2010 after WTI price dislocations due mainly to pipeline constraints.

The spot market and term contracts

The spot market, which captures 40% of internationally traded crude oil, is essentially trading oil cargoes for immediate delivery. That way, the spot market allocates scarce or abundant supplies in an economically efficient manner. A key characteristic of the spot market is that it is pricing the marginal barrel of oil available. The last trade sets the price of oil. That way, the market reflects demand and supply.

An analysis of global oil sales shows that some 60% of all oil produced is internationally traded. Crude oil is the key liquid that meets global consumption of refined products. Of the 100 million barrels per day consumed in 2019, global crude oil production fed 79 million b/d. The balance of liquids mostly comes from natural gas liquids, biofuels and refinery gains.

The prices generated by the crude oil spot market set the price for most of the rest of the market. Pricing formula systems for term contracts link to spot prices. Term contracts, from large producers in the Middle East and else- where, still make up the bulk of the oil sales — close to 60% of all oil sold. Term contracts are essentially a string of spot sales between producers and buyers that have agreed on a certain volume to be shipped during a certain period.

"In the interaction between the Brent ICE Futures contracts and the physical market in the North Sea, the world settles on “the price of oil.” In the end, oil prices are the result of supply and demand. To get there, all the players in the market have to have their say."

In practice, spot sales are often between buyers and sellers that have established relationships, as these deals are still complex to execute. Moving large volumes of oil requires financing, insurance, storage and vessels that are hard to string together on an ad hoc basis. For example, all oil from Angola is sold on a spot basis, but often is bought by the same parties in China. Likewise, the oil produced by the UK and Norway in the North Sea is sold on a spot basis, and much of that to regional buyers that are dealing with the sellers regularly.

Refiners can have term contracts with one or more producers to ensure that they receive a certain volume of crude oil every month, as base-load for their plants. Refineries in regions where short-haul crude is not available, like Asia, use these contracts for security of supply. Refiners go out into the spot market to add additional cargoes.

The rise of the exchanges

The benchmarks Brent and WTI have developed highly liquid markets for prompt and forward supplies that operate at several levels. The most visible are the exchanges that trade the futures contracts — ICE Futures Europe for Brent and CME’s NYMEX for WTI. The benchmarks inspire various markets concurrently.

There is the spot market for immediately deliverable oil, which in practice means loading in a few weeks. The regulated exchanges for futures contracts are reflective of and linked to the spot market and project prices out for a number of years. An informal forward market for crude operates several months ahead for crude delivery. And an unregulated over-the-counter market can design bespoke swaps and options, which allow participants to manage risk or take positions on expected price moves. In addition, Brent has an intricate trading system that links the physical market to the futures contracts, which is discussed in Chapter 4.

The informal and unregulated markets in the oil industry have never been transparent, and have, anecdotally, shrunk in size over time, especially after regulation following the 2008-09 Great Recession that limited their activity and channeled informal risk management toward the regulated exchanges.

The success of the benchmarks

Brent and WTI is linked to their highly liquid exchanges. These ‘paper’ markets — the trade of futures contracts on the exchanges — strengthen the price signals coming from the physical trade of benchmark grades.

It is the relationship between the physical and paper markets where price discovery takes place. In the interaction between the Brent ICE Futures contracts and the physical market in the North Sea, the world settles on “the price of oil.” In the end, oil prices are the result of supply and demand. To get there, all the players in the market have to have their say: producers, consumers, banks and funds, and investors that see oil as a tool to express their market expectations. Because of its strategic importance, crude oil has always attracted political overtones beyond its economic value.

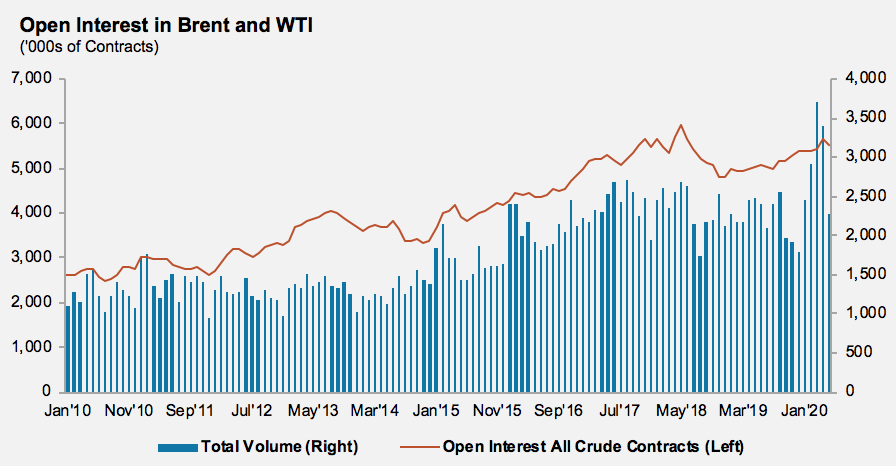

Over the years, the oil exchanges have grown their trading liquidity multifold. The exchanges have seen more activity as crude oil production has grown 22% since 2000, which creates more activity from producers and merchants. Stricter risk management regimes have also created more trading volumes. The exchanges also see more activity from capital flows as oil has attracted more trading from investors. The success of the 5.5 billion barrels of paper crude con- tracts currently open rests upon transparent feedback between the 30 million-40 million b/d of physically traded oil moving in spot markets and the futures markets.

Recent oil market developments

Price shocks have always been a hallmark of the oil market, even when prices were set by governments. Now the price swings are visible on screens in real time and reflective of economic forces of supply and demand and market sentiment. These forces were on unprecedented display when the Covid-19 pandemic struck the world in early 2020. In April, when the economic impact was at its most severe, the coronavirus forced restrictions to travel and trade for nearly half the global population, and impacted nearly 60% of global GDP, the International Energy Agency calculated.

These restrictions caused global oil demand to collapse virtually over- night, pushing it down by 20% on the year in April, Energy Intelligence balances show. As a result, the global oil supply system was disrupted. First, refined product tanks started filling, forcing refineries to stop running crude oil. Demand for jet fuel for planes and gasoline for cars fell in many regions by two-thirds and one- third, respectively. Then, oil producers had to divert cargoes that refineries could no longer accept into storage or even shut in wells.

Both refiners and oil producers followed the fall in demand with a short delay as it took time to wind down operations, and all the oil in the system during this delay went into storage.

By coincidence, April was also the month that Saudi Arabia increased its crude oil exports to high capacity. It was the result of a price war declared in early March after talks with Russia over additional out- put cuts had broken down. Riyadh consequently added 60 million bbl to global oil tanks in April and the additional production and price discounts helped exacerbate the price fall. The policy was reversed for May onward.

The significant influx of supply and sudden demand collapse forced oil prices to follow suit. The front-month Brent contract dropped to an average $26.63 in April, from $55.48 in February when Covid-19 started moving beyond Asia, and $63.67 in January. Prompt prices fell below the price of future supply, providing traders the financial means to store oil that could not be delivered. Prompt prices fell deep enough to allow traders to store oil on land and at sea in very large crude carriers.

In March, April and May the world had to find storage space for more than 12 million b/d — or 1.1 billion bbl, Energy Intelligence reckons, causing global refined product and crude oil stocks to rise 1.3 billion bbl in the first five months of 2020. Crucially, some 200 million bbl went onto vessels. The fear was that the sudden surplus of oil could overflow tanks. The sudden stop of the global economy put tremendous pressure on the oil market.

The oil price discovery process under such duress forced US WTI into negative prices for one day — Apr. 20, the day before contract expiration. The details that caused NYMEX WTI to fall to negative $40 per barrel are subject to study, but essentially too much crude oil was looking for unavailable storage in the pricing and delivery point in Cushing, Oklahoma. The price decline was exacerbated by the forced liquidation of high volumes of contracts when inexperienced retail traders ended up holding too many contracts too close to expiration. Before the pricing debacle, the US had socked away 2 million b/d of oil into tanks without much fanfare. Tankage was still available else- where in the country, but Cushing tanks were filled close to 70% of capacity, and virtually all remaining space was spoken for.

Fears that benchmark Brent could drop below zero like its US counterpart have not materialized. The front-month Brent June contract closed at $25.57 on Apr. 20, and at a low of $19.93 the following day. The seaborne nature of Brent helped stave off calamity, even though the pressure was tremendous. The pressure was absorbed by vessels at sea and within the Brent pricing system. Physical cargoes in the North Sea, without a home due to the sudden demand collapse, traded well below the futures contract and that enabled surplus and distressed oil to find storage.

The pressure on global oil prices and Brent already started in early February, when China’s refineries curbed buying crude in response to Covid-19 and some cargoes remained unsold, with the first North Sea cargoes moving into storage. The culmination of pressure came late April, but the pressure eased as fast as it had appeared. By mid-May, just weeks after WTI fell into negative ter- ritory, the forward price curve signaled that oil supply and demand were reaching a balance and the prompt discount to later supplies had narrowed to a trickle.

Characteristics of Benchmarks

High Physical Volume

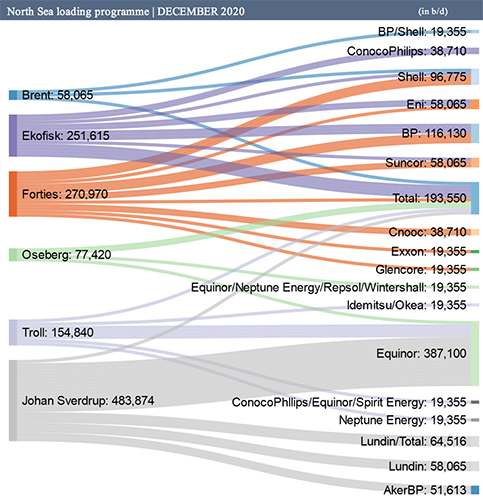

Any benchmark should have robust physically traded volumes under- lying the price assessment. That allows the physical market to provide signals to the futures contracts, and vice versa. Significant liquidity in physical oil cargo trade provides a solid base for high volumes of paper contracts and their offshoots. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) captures physical trades that add up to an estimated 1.6 million barrels per day in spot trade. Much of the WTI-related flows are on a term contract basis and add up to 16 million b/d of crude produced in the US and Canada. The direct physical market for Brent is smaller and needs consistent tweaking. North Sea loading schedules add up to 900,000 b/d and consist of the grades making up the dated Brent assessment — Brent, Forties, Oseberg, Ekofisk and Troll. Global Brent related total spot and term traded volumes are 18.6 million b/d.

The paper market for futures contracts trades at a multiple to that. The WTI and Brent contracts on the ICE and NYMEX platforms com- bined trade a total 2.8 million contracts per day, which represents 2.8 billion bbl of oil. Assuming spot trades of 2.5 million b/d in WTI and Brent combined, the futures contracts can trade at more than 1,000 times the spot trade of oil, hence the need for a solid base. With global oil demand at 100 million b/d, the paper market trades at 28 times the volume of daily oil consumption.

- High Physical Volume: Any benchmark should have robust physically traded volumes underlying the price assessment. That allows the physical market to provide signals to the futures contracts, and vice versa. Significant liquidity in physical oil cargo trade provides a solid base for high volumes of paper contracts and their offshoots.

- Variety of Producers and Sellers: A successful benchmark has a diverse group of producers and sellers so that no single entity can be dominant. For a benchmark that is representative for other grades, no single producer can have too much market influence. In the case of Brent and WTI, the number of producers and sellers is large and diverse.

- Consistent Quality: Benchmark grades must have a consistent quality as the price intrinsically represents the value of the products that can be refined from it. If the quality of the crude fluctuates too much, the price would not reflect the value of the crude.

- Broad Acceptance: For a benchmark to be a guide, it must be accepted by a large group of buyers and represent a crude quality that speaks to the needs of refiners in a wide region. Both Brent and WTI are light, sweet oil and broadly accepted. They are also both easy to refine, which increases their popularity.

- Benchmarks and Reference Grades: Brent and WTI are the world’s major benchmarks. They have attracted the deep financial markets that solidify their usefulness and status. They are so overwhelming that they overshadow all other initiatives trying to gain market share. Creating benchmarks takes time. In the Middle East, Dubai and Oman are benchmarks for pricing medium, sour oil. But they essentially trade at a differential versus Brent. Trade in Dubai and Oman fine-tunes the spread versus Brent as expressions of the quality differential between sweet and sour grades and the geographic differential between the Atlantic Basin and Asia.

The actual volume of crude that would be sufficient to call a market liquid is always a matter of debate. In practice, benchmarks allow for a number of related crude grades to be traded and delivered into them. The key is that no one party can dominate the trade and skew the price.

Preferences for the dominant benchmark can change over time, when produced volumes dry up or traded volumes dip. The first need for reference grades arose when the spot market started expanding from a niche 5% of all trades at the end of the 1970s and start of the 1980s. These reference grades were created to satisfy the market’s need for guidance on the value of crude oil as governments no longer controlled the oil price.

The market quickly settled on Arab Light from Saudi Arabia and UK Forties in the North Sea. Arab Light was the natural international benchmark because of its prominent role within OPEC as the key reference grade for its pricing system. Also, refineries in the US, Europe and Asia were all buying it. Arab Light still has the volume to be a global benchmark with production between 4 million and 5 million b/d but the Saudi government curbed its spot sales. The government in Riyadh didn’t want to set the price of oil; it would instead link its sales to regional spot grades. To this day it sells its oil only under term contracts linked to regional benchmarks like Brent in the North Sea, the Argus Sour Crude Index in the US and Oman/Dubai in Asia.

Parallel, Forties served as the North Sea benchmark due to its production volumes, but it was quickly overtaken by Brent when its volumes started rising. Over the years, keeping sufficient trading volumes has always been an issue for Brent, requiring creative solutions. When Brent volumes started declining in the late 1980s, it added the Ninian field and became Brent Blend. A decade later, low volumes again plagued the Brent bench- mark, which was resolved by allowing alternative pricing off similar-quality Forties and Norwegian Oseberg, later followed by Norwegian Ekofisk and Troll. The benchmark kept Brent as the brand name.

But around the mid-1980s, the market picked another benchmark. US WTI became the marker almost by default. It was selected in 1983 as the main deliverable and reference grade for the new NYMEX crude oil futures contract. That caught on and put a spotlight on WTI ever since. From the beginning, WTI was ill-suited to be a global bench- mark because of its landlocked status in Cushing, Oklahoma and its inability to be exported due to US law. Regional incidents like a pipe- line rupture or refinery outage could also impact the global price of oil. However, large volumes of contracts on the exchange and long opening hours made up for its flaws.

The physical volumes of produced and traded WTI have always been somewhat unclear, as wells spaced closely together could produce various qualities, like WTI from one well and West Texas Sour from another. But the number of physical trades were always high, which was reflected in high volumes on the NYMEX. The NYMEX contract rules say that all blends of oil that meet a list of specifications, including sulfur content, gravity, total acid number and metal content, are deliverable into the contract. In Cushing, Oklahoma, where the NYMEX contract gets priced and delivered, WTI is essentially domestic sweet oil.

Variety of producers and sellers

A successful benchmark has a diverse group of producers and sellers so that no single entity can be dominant. For a benchmark that is representative for other grades, no single producer can have too much market influence. In the case of Brent and WTI, the number of producers and sellers is large and diverse.

The grades making up dated Brent, a spot cargo of Brent with a loading date, are North Sea grades Brent, Forties, Oseberg, Ekofisk and Troll. The largest active traders in recent Brent deals were Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Exxon Mobil, Total, Eni, Suncor, ConocoPhillips, China National Offshore Oil Corp., EnQuest and Vitol.

In the case of WTI, the number of producers is large and every producer that can deliver a crude with the deliverable qualities of the contract specification is a seller. Dozens of at times small producers trade physical volumes on a daily basis. There are no dominant parties. The US Commodity Futures Trading Commission sees more than 70 producers actively hedging in WTI futures. The same data notes that 60 banks and funds are taking financial positions — and they represent thousands of investors and speculators.

Consistent quality

Benchmark grades must have a consistent quality as the price intrinsically represents the value of the products that can be refined from it. If the quality of the crude fluctuates too much, the price would not reflect the value of the crude. Other crude grades establish price relationships to benchmarks. A crude of superior quality to the benchmark would trade at a premium to it, while a crude with an inferior quality would trade at a discount.

To maintain these pricing relationships, it is important that the benchmark is the stable crude that guides other grades. In the case of North Sea production, various fields can flow into one stream. The quality of Forties can change, especially when it’s key Buzzard field, which is more sour than the other fields, changes volumes. That matters since it often sets the price of dated Brent. The market understands the implication of the quality changes in Buzzard, and when these are flagged in advance, pricing adjusts smoothly.

The crudes deliverable in the WTI contract have to comply with a set of strict rules as spelled out in the CME/NYMEX delivery handbook. These rules have been made more specific over time at the request of refiners so producers or traders could not blend inferior qualities into a batch and still meet contract specifications.

Broad Acceptance

For a benchmark to be a guide, it must be accepted by a large group of buyers and represent a crude quality that speaks to the needs of refiners in a wide region. Both Brent and WTI are light, sweet oil and broadly accepted. They are also both easy to refine, which increases their popularity.

Brent’s ability to sail around the world makes it attractive as a price guide beyond the North Sea. Producers in the North Sea and Mediterranean as well as those in West Africa have linked their sales to Brent for years. The move east followed later. In 2011, Malaysia’s national oil company Petronas adopted dated Brent as the sole benchmark for its crude production, including its flagship Tapis grade. By the beginning of 2012, all Australian crude and condensate was priced against Brent. Papua New Guinea and Vietnam also followed, as did the Philippines. WTI is a known quality in the US and has been accepted in the wider world after the US lifted export restrictions late 2015.

The price of both contracts fluctuates on geopolitical tensions. But Brent and WTI are not subject to artificial production cuts from government or national oil companies under OPEC agreements, which would distort the price discovery and undermine the benchmark’s status. Competing Mideast grades, and now Russian exports, are impacted by such cuts under rules from OPEC and allied producers.

Broad acceptance is to a large degree helped by the financial market makers. If the spot trade is solid and a paper market can develop on that basis, it becomes attractive for producers and consumers to hedge, and for banks and funds to pledge risk capital. Committed capital in futures contracts creates open interest and confidence in a market’s future stability. High volume ensures traders can quickly enter and exit positions with minimal price slippage. Both are sup- ported by investment and trade in the underlying physical commodity. And both are crucial to liquidity. Once a financial oil market is established, its depth and new, linked derivatives create even more liquidity. Liquidity of the financial instruments is crucial to trade and the industry. Both Brent and WTI have a deep paper market.

Benchmarks and Reference Grades

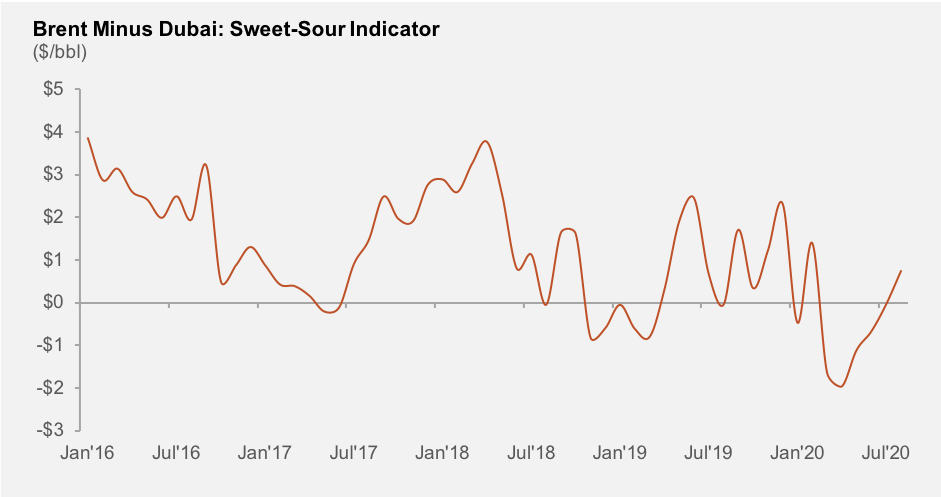

Brent and WTI are the world’s major benchmarks. They have attracted the deep financial markets that solidify their usefulness and status. They are so overwhelming that they overshadow all other initiatives trying to gain market share. Creating benchmarks takes time. In the Middle East, Dubai and Oman are benchmarks for pricing medium, sour oil. But they essentially trade at a differential versus Brent: Brent sets the price and trade in Dubai and Oman fine-tunes the spread versus Brent as an expression of the quality differential between sweet and sour grades. That makes Dubai and Oman good benchmarks for sour oil, but they take their flat price from Brent.

The Dubai price is connected to Brent through the Exchange of Futures for Swaps (EFS), and is hence essentially derived from it. A Brent-Dubai EFS is virtually identical to a Brent EFP, except that instead of exchanging a futures position for a physical one, futures are exchanged for a swap. The Brent-Dubai EFS represents the spread between Brent futures and the Dubai cash market, which is under- pinned by the Dubai intermonth swap spreads.

The Brent-Dubai spread is one of the main criteria that dictates the viability of physical arbitrage between the Atlantic basin and Asia. A lower Brent premium — that is, a weakening of the EFS — signals an increasing financial incentive to move sweet crude produced in the Atlantic Basin (including not only North Sea oil but also West African crude) to markets East of Suez.

Oman is traded as a futures contract on the Dubai Mercantile Exchange. It rose in status in 2018 when Saudi Arabia took the Oman price from the DME as part of its price link for Asian sales, along with the S&P Global Platts assessment of Dubai, which has its own futures contract trade on ICE. The DME contract is supported by Saudi Arabia, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Kuwait. Volumes and open interest in the contract remain limited at a fraction of what is traded in London and New York. Oman and Dubai are key for pricing term contracts to Asia. In the region, the UAE is in the process of establishing its own market with ICE Futures Abu Dhabi based on its Murban export grade.

When a region looks at a crude stream for a regional price guide, such a stream is a reference grade. In the US Gulf of Mexico, Mars Blend is a quick reference for the value of a medium, sour grade. Mars is the key ingredient for the Argus Sour Crude Index for the region, which in turn trades at a differential versus WTI. In Europe, Russian Urals are a quick reference for the value of a medium, sour barrel in Northwest Europe and the Mediterranean. Urals trades at a differential versus dated Brent, mostly at a discount to express the lower quality of Urals. In Asia, as assessed by pricing firm Platts, Dated Brent started reporting Asian prices starting in 2008, making inroads in the growing market.

In China, the International Energy Exchange (INE) in Shanghai started trading the country’s first oil contract in March 2018. The government in Beijing has long pushed for an oil contract priced in Chinese yuan to reflect the country’s growing importance as the world’s largest oil importer since 2017, and to give it a bigger say in the crude price discovery process. It is designed to reflect the delivered price of a barrel of medium, sour oil. Trading volumes and open interest are growing, but the contract remains small compared to Brent and WTI. The contract has attracted more open interest during the Covid-19 pandemic with a total 170,000 lots along the curve, but that is still less than 10% of Brent and WTI. The contract is popular with onshore retail clients who use it as a currency hedge and to bet on oil prices. In trading volume, the contract is third after WTI and Brent. At times, retail clients on the exchange have bid up the contract above physical prices that can be delivered into the contract. For example, the July INE contract traded $9 per barrel over the DME June contract. The INE has increased storage capacity associated with the exchange to 29 million bbl to accommodate refineries that want to take delivery through the contract.

Differences between Brent and WTI

For many years, NYMEX WTI was characterized as the world’s financial benchmark, while Brent was seen as the benchmark of physical trade. The characterization was somewhat of a misnomer, since WTI is the physically settled contract while Brent is financially settled — although it has the ability to physically deliver through trading mechanisms. But the characterization expressed the large volumes in the NYMEX WTI futures contract, while Brent sailed across the globe and impacted actual crude oil prices, but lacked the financial clout of its US counterpart.

A decade ago, the rise of US shale production started to undermine WTI’s dominance as the contract gaining the most attention. The unexpected and rapid growth of US oil production put huge strains on the US pipeline systems that connect to landlocked Cushing. Distressed US crude and rising inventories in Cushing pushed WTI to discounts versus similar crudes in the US not impacted by pipe- lines. At the same time, it also impacted prices of grades around the world. This undermined its status and attractiveness as global benchmark.

As a result, the benchmark stopped to accurately represent the value of crude oil. WTI’s steep discounts made Brent the de facto global benchmark. That switch was not much of a stretch since much of the world was already pricing its crude off Brent. The switch highlighted the inherent differences between the two benchmarks. The landlocked status of WTI that can disconnect from the world, and its attraction to financial players, came into greater focus. Around that time, Brent had sorted out another bout with trading liquidity and established a better base for spot assessments. That Brent could sail around the world — particularly to Asia, where much of the oil ended up — turned into a key advantage.

Resources

RESEARCH REPORT

Global Crude Benchmarks: Brent Sets the Standard Part 1

In their executive summary, Energy Intelligence explores the role of Brent and WTI crude oil benchmarks, their mutual relationship and their interaction with the global oil market.

RESEARCH REPORT

Global Crude Benchmarks: Brent Sets the Standard Part 3

Part three closes out the series with Brent’s evolution, its markets and why commercial and non-commercial participants rely on it.

Article

Brent vs WTI

ICE’s Head of Oil Market Research, Mike Wittner, looks into why WTI went negative and whether it could happen to the global crude benchmark, Brent.

RESEARCH REPORT

Global Crude Benchmarks: Brent Sets the Standard Part 1

In their executive summary, Energy Intelligence explores the role of Brent and WTI crude oil benchmarks, their mutual relationship and their interaction with the global oil market.

RESEARCH REPORT

Global Crude Benchmarks: Brent Sets the Standard Part 3

Part three closes out the series with Brent’s evolution, its markets and why commercial and non-commercial participants rely on it.

Article

Brent vs WTI

ICE’s Head of Oil Market Research, Mike Wittner, looks into why WTI went negative and whether it could happen to the global crude benchmark, Brent.